Mice Display First-Aid Behaviors: Uncovering the Neurobiology and Evolution of Prosociality in Rodents

Researchers have documented mice performing what can only be described as "first aid" on unconscious companions.

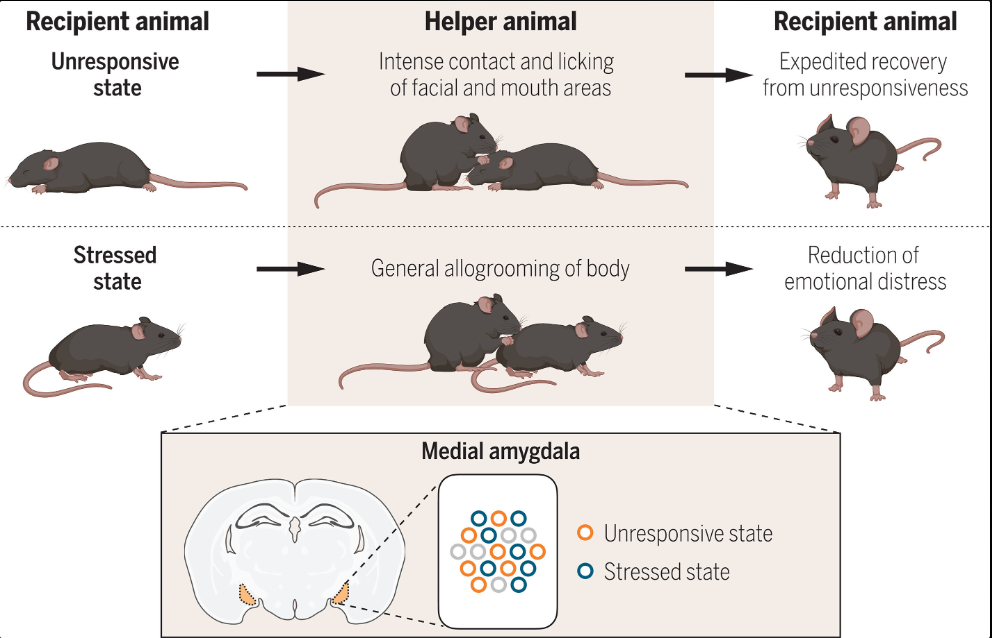

In a groundbreaking discovery that challenges our understanding of animal cognition, researchers have documented mice performing what can only be described as "first aid" on unconscious companions. This behavior—observed in controlled laboratory settings—includes tugging on tongues, clearing airways, and diligently grooming unresponsive peers. Published in Science by Wenjian Sun, Guang-Wei Zhang, and colleagues, these findings rewrite assumptions about the complexity of prosocial behavior in small mammals and open new avenues for exploring the evolutionary roots of empathy.

The Discovery: A Rodent Rescue Protocol

When encountering an unconscious cage mate, mice engage in a stereotypic sequence of actions reminiscent of human first responders:

- Assessment Phase: The helper mouse begins with intense sniffing around the face and throat, likely detecting chemical cues of distress.

- Airway Management: Over 50% of cases involve pulling the unconscious mouse’s tongue outward—a critical step for opening airways.

- Debris Removal: Helper mice often bite or nudge the mouth area to expel foreign objects before addressing the tongue.

- Recovery Support: Continuous grooming follows until the peer regains mobility.

Notably, these behaviors emerge only toward unresponsive individuals. Mice ignore sleeping peers and prioritize familiar companions over strangers, suggesting intentionality rather than reflexive action.

Why Mice Perform “CPR”: Survival Advantages

The study’s most striking finding lies in the tangible survival benefits of this interspecies care:

- Faster Recovery: Anesthetized mice receiving assistance regained consciousness 40% faster than isolated controls.

- Predator Defense: Quick revival reduces the group’s exposure time to threats—a critical advantage in wild populations.

- Social Bonding: Familiar mice receive more vigorous assistance, reinforcing group cohesion and reciprocal care networks.

This behavior aligns with evolutionary theories of kin selection, where aiding genetically related individuals enhances gene propagation. However, the preference for familiar (not necessarily related) peers hints at a more nuanced social calculus.

The Neuroscience of Rodent Altruism

Delving into the brain mechanisms, researchers identified two interconnected systems driving this prosociality:

1. Oxytocin-Driven Motivation

- Hypothalamic PVN: Oxytocin-producing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus activate upon detecting a peer’s distress.

- Amygdala Integration: These signals merge with social memory circuits, prompting help toward recognized individuals.

Blocking oxytocin receptors abolished helping behaviors, even among cage mates, confirming the hormone’s pivotal role.

2. Brainstem Rescue Circuit

A newly discovered pathway directly links sensory input to revival actions:

- Tongue Mechanoreceptors → Mesencephalic Trigeminal Nucleus → Locus Coeruleus (NE neurons)

This circuit bypasses higher cognition centers, enabling rapid airway clearance and noradrenaline-mediated arousal in the unconscious mouse.

Evolutionary Implications: Prosociality’s Ancient Roots

The presence of structured helping behavior in mice suggests that prosociality predates primate social complexity by millions of years. Key evolutionary insights include:

- In-Group Bias: Helping familiar peers mirrors early human tribal cooperation, where group survival trumped individual risk.

- Oxytocin Conservation: Shared neuroendocrine pathways (e.g., oxytocin in bonding) across mammals imply a common evolutionary origin.

- Situational Altruism: Mice weigh energy costs against social bonds—assisting only when the peer’s survival probability justifies effort.

This bridges the gap between “selfish gene” theories and cooperative evolution, showing how even simple organisms balance self-preservation with group welfare.

Human Applications: From Neuroscience to Robotics

Beyond academic fascination, these findings have tangible applications:

- Mental Health: Dysfunctional oxytocin pathways are implicated in autism and schizophrenia. Mouse models could test therapies targeting social motivation.

- Search-and-Rescue Robotics: Mimicking the brainstem’s efficient sensory-motor circuit could improve machines’ emergency response algorithms.

- Animal Welfare: Zoos and labs might use unconscious conspecifics to assess captive animals’ stress and social health.

Controversies and Ethical Questions

While revolutionary, the study sparks debate:

- Anthropomorphism Risk: Are we projecting human traits onto rodents? Lead author Wenjian Sun argues that objective metrics (recovery speed, neural activation) validate the comparison.

- Pain vs. Help: Biting an unconscious peer’s mouth could be selfish exploration rather than aid. However, the precise targeting of airway obstruction points to deliberate intent.

Future Research Directions

Ongoing studies aim to:

- Map genetic factors influencing helping behavior intensity.

- Test if mice assist other species (e.g., injured rats).

- Develop optogenetic tools to activate rescue circuits artificially.

Conclusion: Rethinking Animal Intelligence

This study shatters the notion that sophisticated prosociality is unique to primates. By integrating neurobiology, behavior, and evolutionary theory, it paints mice as calculated altruists—balancing risks to aid peers in ways that echo human first aid. As we uncover more about these tiny heroes, we may find that empathy’s roots run deeper and wilder than ever imagined.

- Sun, W., Zhang, G.-W., et al. (2023). Revival of anesthetized mice through prosocial救助 behavior. Science.

- Insel, T.R. (2010). The challenge of translation in social neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Carter, C.S. (2014). Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology.

- Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray.